Chi è Seamus Heaney?

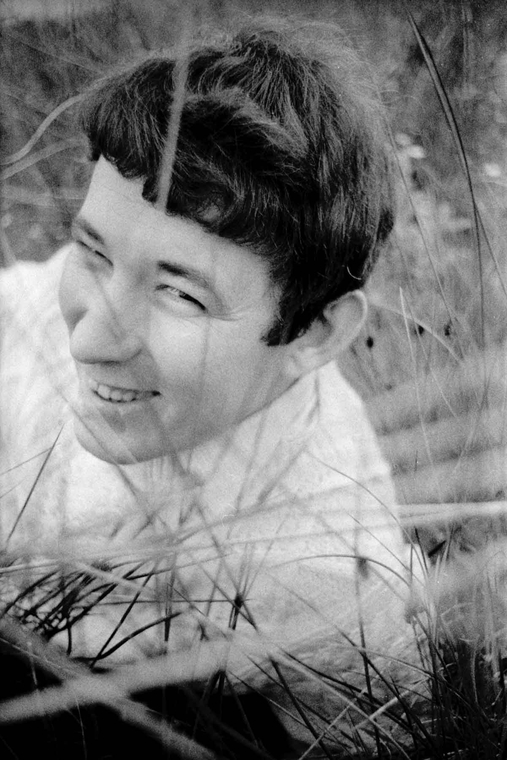

Figlio di contadini cattolici, Seamus Heaney (Castledawson, 13 aprile 1939 – Dublino, 30 agosto 2013) vive fin da piccolo a stretto contatto con la vita rurale dell’Ulster. Nelle sue raccolte di poesie troviamo momenti di vita vissuta nella fattoria di Mossbawn a County Derry, che si alternano a tematiche nazionali, in particolare alle continue e sanguinose lotte tra cattolici e protestanti. Dal 1957 al 1961, un ormai ventenne Heaney, frequenta i corsi di letteratura inglese alla Queen’s Univerity di Belfast, ed inizia a scrivere poesie ispirate da Hopkins e Keats, usando lo pseudonimo di Incertus. A tal proposito Peter Sirr in In step with what escaped me: the poetry of Seamus Heaney afferma:

Figlio di contadini cattolici, Seamus Heaney (Castledawson, 13 aprile 1939 – Dublino, 30 agosto 2013) vive fin da piccolo a stretto contatto con la vita rurale dell’Ulster. Nelle sue raccolte di poesie troviamo momenti di vita vissuta nella fattoria di Mossbawn a County Derry, che si alternano a tematiche nazionali, in particolare alle continue e sanguinose lotte tra cattolici e protestanti. Dal 1957 al 1961, un ormai ventenne Heaney, frequenta i corsi di letteratura inglese alla Queen’s Univerity di Belfast, ed inizia a scrivere poesie ispirate da Hopkins e Keats, usando lo pseudonimo di Incertus. A tal proposito Peter Sirr in In step with what escaped me: the poetry of Seamus Heaney afferma:

Heaney famously signed his early poems ‘Incertus’, the uncertain one, as if he didn’t quite believe his own gift, but an uncertainly principle is built into the work from the start, a kind of duality between affirmation and doubt, imaginative freedom and constraint, that in itself becomes part of the drama of the poetry.[…] The narrative of Heaney’s poetic career runs parallel to the political disintegration of Northern Ireland and the ensuing violence[…] Heaney has had to bear the weight of public expectation[…] the poetry should somehow answer to violence, division, rupture, that the poet speaks out of the public domain, that his voice must somehow be representative[1].

Negli anni successivi insegna a Belfast ed entra in contatto con la poesia di Patrick Kavanagh che influenzerà la sua produzione poetica. Primo di nove fratelli, egli racconta la sua infanzia nel discorso tenutosi in Svezia durante le cerimonie per il Nobel, rievocando i suoni che lo hanno accompagnato nella sua crescita. In Crediting Poetry Heaney afferma:

In the nineteen forties, when I was the eldest child of an ever-growing family in rural Co. Derry, we crowded together in the three rooms of a traditional thatched farmstead and lived a kind of den-life which was more or less emotionally and intellectually proofed against the outside world. It was an intimate, physical, creaturely existence in which the night sounds of the horse in the stable beyond one bedroom wall mingled with the sounds of adult conversation from the kitchen beyond the other

[…]We could pick up the names of neighbours being spoken in the local accents of our parents, and in the resonant English tones of the newsreader the names of bombers and of cities bombed, of war fronts and army divisions, the numbers of planes lost and of prisoners taken, of casualties suffered and advances made; and always, of course, we would pick up too those other, solemn and oddly bracing words, “the enemy” and “the allies“. […]The wartime, in other words, was pre-reflective time for me. Pre-literate too. Pre-historical in its way.[…][2]

Inoltre, Heaney sceglie di aprire la sua prima raccolta di prose, Preoccupations, pubblicata nel 1980, con il testo “Mossbawn”. Comincia con la parola greca omphalos, che significa ombelico, e di qui la pietra che segna il centro del mondo, che per il poeta è la contea di Derry, Heaney racconta: “I bombardieri americani rombano verso l’aerodromo di Toomebridge, le truppe americane manovrano nei campi lungo la strada, ma tutta quella grande impresa storica non disturba i ritmi del cortile. E li sta la pompa, un sottile idolo in ferro con l’elmetto e il muso sporgente, con un’ampia impugnatura, dipinto di verde scuro e piantato su un basamento in cemento, a segnare il centro di un altro mondo.”[3] L’importanza di ripercorrere la sua infanzia, sta nel fatto che tutta la sua produzione poetica è pervasa da immagini mnesiche, la memoria ha una funzione evocatrice per il poeta, che scava nel passato. In un articolo del 1972, incluso in Preoccupations, Heaney descrive la sua posizione di poeta nordirlandese cresciuto in lingua inglese, affermando di parlare e scrivere in inglese, ma di non condividere interamente le attenzioni e le prospettive di un inglese. Egli utilizza il termine home, per sottolineare di non sentirsi parte di tale tradizione e aggiunge “I live off another hump as well”. Il termine hump (“collinetta”,” altura”,”rilievo”, ma anche “malinconia” e “depressione”), in questo caso, seguendo la traduzione di Piero Vaglioni, significa “mammella” e posto accanto a “casa” è un chiaro riferimento alla madrepatria, quell’Irlanda tanto amata e sempre cantata nei suoi versi.[4]

Inoltre, Heaney sceglie di aprire la sua prima raccolta di prose, Preoccupations, pubblicata nel 1980, con il testo “Mossbawn”. Comincia con la parola greca omphalos, che significa ombelico, e di qui la pietra che segna il centro del mondo, che per il poeta è la contea di Derry, Heaney racconta: “I bombardieri americani rombano verso l’aerodromo di Toomebridge, le truppe americane manovrano nei campi lungo la strada, ma tutta quella grande impresa storica non disturba i ritmi del cortile. E li sta la pompa, un sottile idolo in ferro con l’elmetto e il muso sporgente, con un’ampia impugnatura, dipinto di verde scuro e piantato su un basamento in cemento, a segnare il centro di un altro mondo.”[3] L’importanza di ripercorrere la sua infanzia, sta nel fatto che tutta la sua produzione poetica è pervasa da immagini mnesiche, la memoria ha una funzione evocatrice per il poeta, che scava nel passato. In un articolo del 1972, incluso in Preoccupations, Heaney descrive la sua posizione di poeta nordirlandese cresciuto in lingua inglese, affermando di parlare e scrivere in inglese, ma di non condividere interamente le attenzioni e le prospettive di un inglese. Egli utilizza il termine home, per sottolineare di non sentirsi parte di tale tradizione e aggiunge “I live off another hump as well”. Il termine hump (“collinetta”,” altura”,”rilievo”, ma anche “malinconia” e “depressione”), in questo caso, seguendo la traduzione di Piero Vaglioni, significa “mammella” e posto accanto a “casa” è un chiaro riferimento alla madrepatria, quell’Irlanda tanto amata e sempre cantata nei suoi versi.[4]

Bernard O’Donoghue, spiega che nel 1974, Robert Lowell definì Heaney the best Irish poet since Yeats ma aggiunge che una domanda da porsi è cosa si intenda per “Irish poet”; Un poeta irlandese a prescindere dall’argomento trattato, oppure un poeta che scrive in irlandese, o ancora un poeta impegnato a scrivere con la consapevolezza di una tradizione poetica irlandese precedente? [5] A tutto ciò Heaney ha più volte risposto rigettando l’etichetta di British poet, per esempio ripensando agli anni tra i banchi di scuola, scrive:

Il linguaggio letterario, la parola raffinata dei canoni della poesia inglese, era una specie di alimentazione forzata. Non ci deliziava riflettendo le nostre esperienze; non rimandava l’eco delle nostre parole in strutture regolari e sorprendenti. Le lezioni di poesia, infatti, erano un po’ come le lezioni di catechismo: un inculcare ufficiale di formule consacrate che in qualche modo avrebbero dovuto esserci utili nella vita da adulti che ci si stendeva davanti.[…] In entrambi i casi eravamo intimiditi dalle dimensioni del suono […][6]

Nell’ introduzione alla traduzione di Beowulf (2000), Heaney afferma:

When I was an undergraduate at Queen’s university, Belfast, I studied Beowulf and other Anglo-Saxon poems and developed not only a feel of the language, but a fondness for the melancholy and fortitude that characterized the poetry[7].

Egli accetta l’invito proveniente dagli editori della Northon Anthology of English Literature a tradurre il poema anglosassone, pur consapevole che si tratta di un “labor-intensive work”. Egli continua:

Even so, I had an instinct that it should not be let go. An understanding I had worked out for myself concerning my own linguistic and literary origins made me reluctant to abandon the task. I had noticed for example, that without any conscious intent on my part certain lines in the first poem in my first book conformed to the requirements of Anglo-Saxon metrics. These lines were made up of two balancing halves, each half containing two stressed syllables- The spade sinks into gravelly ground:/ My father digging. I look down… ”- and in the case of the second line there was alliteration linking “digging” and “down” across the caesura. Part of me in other words, had been writing Anglo-Saxon from the start. […] Sprung from an Irish nationalist background and educated at a Northern Irish Catholic school, I had learned the Irish language and lived within a cultural and ideological frame that regarded it as the language that I should by rights have been speaking but I have been robbed of.[…][8]

Il contatto con il testo di Beowulf fa riemergere nella memoria del poeta i suoni delle sue origini e la consapevolezza di non poterne fare a meno, infatti Heaney riflettendo con una visione a posteriori sulla poesia che apre la prima raccolta Death of a Naturalist, si rende conto di come la metrica anglosassone facesse parte del suo voice right fin dall’inizio.

Il contatto con il testo di Beowulf fa riemergere nella memoria del poeta i suoni delle sue origini e la consapevolezza di non poterne fare a meno, infatti Heaney riflettendo con una visione a posteriori sulla poesia che apre la prima raccolta Death of a Naturalist, si rende conto di come la metrica anglosassone facesse parte del suo voice right fin dall’inizio.

Ci lascia tristemente a Dublino il 30 Agosto 2013, pronunciando queste ultime parole “Don’t be afraid“.

[1] Peter Sirr, In step with what escaped me, pp. 8,9

[2] Seamus Heaney, Crediting Poetry, Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1995

[3] Seamus Heaney, Mossbawn in Attenzioni, Preoccupations- Prose Scelte 1968-1978,introduzione e cura di Massimo Bacigalupo, traduzione di Piero Vaglioni, Fazi Editore, Roma, 1996 p. 5

[4] Cfr Andrew Sanders, Storia della Letteratura Inglese,dal secolo XIX al postmoderno, a cura di Anna Anzi, Mondadori Università, 2001, p. 376-379

[5] Bernard O’Donoghue, Seamus Heaney and the language of poetry, Biddles Ltd, Guilford and King’s Lynn, Great Britain, 1994 pp. 25,26

[6] Cfr Seamus Heaney, Mossbawn in Attenzioni, Preoccupations- Prose Scelte 1968-1978,introduzione e cura di Massimo Bacigalupo, traduzione di Piero Vaglioni, Fazi Editore, Roma, 1996, p. 18

[7] Cfr Seamus Heaney, The Text of Beowulf, A Verse Translation, W.W. Norton & Company, 2001, p. xxxii-xxxiv

[8] Cfr Seamus Heaney, The Text of Beowulf, A Verse Translation, W.W. Norton & Company, 2001, p. xxxii-xxxiv